- Inventory of slaves in Detroit, Michigan. Joel Thurtell photo of record in Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

By Joel Thurtell

Just as I predicted in a January 2007 Detroit Free Press story, Grosse Ile’s historians changed history.

But not the way I expected.

Early in 2007 (I retired from my Free Press reporting job the following November), the people who manage historical perceptions on the Big Island led me to believe that they were going to include the slavery aspect of their community’s past in a book they were preparing about Grosse Ile history.

Instead of publishing the facts, they chose to censor.

In Part II of my series, “Tomatoes & Eggs,” I’ll reproduce my review of the Grosse Ile Historical Society’s book.

And I’ll explain “Tomatoes & Eggs.”

With permission from the Detroit Free Press, here is the first installment of a series about local control of history.

Headline: HISTORY TELLS TALE OF SLAVES ON GROSSE ILE

Sub-Head: BUT MANY DETAILS ARE STILL A MYSTERY

Byline: BY JOEL THURTELL FREE PRESS STAFF WRITER

Pub-Date: 1/21/2007

Memo: DOWNRIVER

Correction:

Text: On Grosse Ile, they’re changing history.

Or at least they’re changing the way it’s written.

They plan to mention that black and American Indian slaves once lived

on the island.

Sarah Lawrence and Ann Bevak are working on the Grosse Ile Historical

Society book, and this information wasn’t on their radar.

Now it is.

Lawrence is editing the book, and Bevak is working on the early

history chapter.

Once I shared the results of my research with Bevak, she grasped the

possibilities, like reproducing the 1796 price list of slaves.

“It’s the kind of thing people will latch onto,” she said.

They aren’t the only Grosse Ile folks who are only now hearing about

this, even though human chattels were a part of daily life on Grosse

Ile for sure before 1796, and maybe later. That’s the year Britain

turned Michigan over to the fledgling United States. It’s also when

the largest holder of slaves in Michigan died.

After the death of William Macomb, his heirs itemized all his

property – cows and horses, copper fish kettles, a beehive, a pair of

saddlebags and 26 slaves.

Twenty years earlier, William Macomb and his brother, Alexander

Macomb, bought Grosse Ile from Indians. I wrote about the Macomb

(pronounced Macoom) brothers a couple of years ago and got an e-mail

from Bill McGraw, a fellow Free Press reporter, who wondered if I knew

that William Macomb had been a slave-owner.

I didn’t.

At that point, McGraw contended that historians have written little or

nothing about this aspect of Michigan history.

Seems he’s right.

The Macomb brothers have descendants on Grosse Ile, and they didn’t

know about it. The brothers were the

great-great-great-great-grandfathers of Connie de Beausset. (Two of

the brothers’ children, who were first cousins, married and de

Beausset is their descendant.) Her family owns the oldest working

farm in Michigan to stay in one family; the farm specializes in

azaleas and rhododendrons.

“No, I can’t be any help to you at all on that,” Connie de Beausset

told me. “I haven’t heard anything about any slaves.”

Her daughter, who runs the family’s Westcroft Gardens, was surprised too.

“No, I wasn’t aware of them having slaves at all,” said Denise de

Beausset. “That’s funny; you’d think there would have been talk about

slaves running the farm. Nobody ever talks about it on our side. I

wonder if it was out of embarrassment or it wasn’t politically

correct. Nobody ever talked about slaves.

“I’ll be darned.”

I found the inventory of William Macomb’s property in the Detroit

Public Library’s Burton Historical Collection. The list is quite long,

and includes two oxen valued at 24 New York pounds; four cows, 40

pounds; a pair of andirons, 4 pounds, and a stovepipe, 25 pounds.

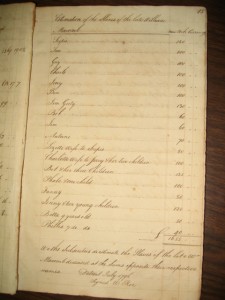

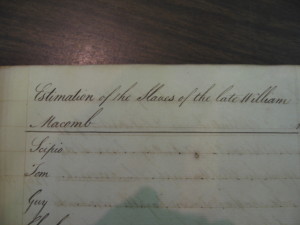

It has an “Estimation of the Slaves of the late William Macomb.” Most

esteemed were two slaves named Scipio and Jim Girty, each valued at

130 New York pounds. Ben was worth 100 pounds. Bel was priced at 135

pounds, but that included her three kids. Bob was worth 60 pounds.

Phillis was worth 40 pounds, though she was only 7 days old.

Jerry was valued at 100 pounds and his wife, Charlotte, with her two

children, was priced at 100 pounds.

But here’s the interesting thing about Charlotte: In 1793 and 1794,

the Macomb house on Grosse Ile was “in charge of Charlotte,” wrote

Isabella Swan in “Deep Roots,” her history of Grosse Ile. “Charlotte

had been with the Macombs as early as 1788,” wrote Swan.

Charlotte was boss of the farm, but still, after her owner’s death,

she was cataloged along with William Macomb’s 25 other human pieces of

property.

“I’ve never heard that name Charlotte,” Connie de Beausset told me.

What happened to Charlotte and the other 25 Macomb slaves? Letters in

the Burton Collection, written by William Macomb before his death,

show that he was in the habit of buying and selling slaves.

On Jan. 12, 1790, Macomb acknowledges partial payment for “a negro wench.”

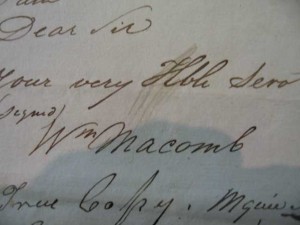

He wrote on Aug. 17, 1789, that “I have taken the liberty to address

to your care Two negroes a Woman & a man the property of Mr. Alexis

Masonville. They are to be disposed of at your place for 200 pounds

New York currency. I cannot say much in their favor as to honesty,

more particularly of the woman she is very handy & a very good cook.

The man is a very smart active fellow & by no means a bad slave.

“I hope you may be able to dispose of them at your place & remit to me

the money. I do not wish they should be dispose of to any person

doubtful or on a longer credit than the first of June next – I am Dear

sir your very Able servant Wm Macomb.”

The Ordinance of 1787 banned slavery in the new territories that would

become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Michigan. But slaves belonging to

British settlers were still allowed. The 1810 census showed 17 slaves

still in Detroit, according to the American Legal History Network Web

site www.geocities.com/michhist/detroitslave.html?20079, and in 1818,

the Wayne County assessor was still taxing slaves as property.

On Grosse Ile, African Americans weren’t the only slaves. According to

Swan, there may have been an enslaved Indian on the island about 1795.

“The Indians who were slaves had been taken captive in inter-tribal

wars and sold to the whites. Those who held slaves when the Americans

took over were allowed to retain them,” wrote Willis Dunbar in

“Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State.”

With historical documents and publications to refer to, the Grosse Ile historians can use

the information about slavery in their book, to be published by Arcadia Publishing in

Chicago.

“I think that would be a good part for the book,” said Denise de

Beausset “That’s a really big part of the history of the island, that

it’s not just the rich and famous that moved here later.”

Great. Now I have another assignment for you Grosse Ile historians.

Under “slaves” in the index of Isabella Swan’s book there’s a

reference to pages 37-38: “Ben and Dan escape.”

Well, Ben and Dan made such a clean getaway that I can’t find mention

of them on either of those pages. Can somebody tell me the story of

those fugitive slaves, Ben and Dan?

Caption: 2005 photo by MARY SCHROEDER / Detroit Free Press

Connie de Beausset holds a copy of the treaty that the Macombs and the

Indians signed giving the Macombs the right to Grosse Ile. Although de

Beausset is a descendant of the Macombs, neither she nor her daughter,

Denise de Beausset, had known of the existence of family slaves.

JOEL THURTELL / Detroit Free Press

William Macomb’s signature on a letter relating to the sale of two slaves.

JOEL THURTELL / Detroit Free Press

“Estimation of the Slaves of the late William Macomb,” from the

inventory of Macomb’s property.

2005 photo by KATHLEEN GALLIGAN / Detroit Free Press

A Historical Commission marker stands on the Grosse Ile site of the

state’s oldest continuously working farm. Its owners are descendants

of William Macomb.

Illustration: PHOTO

Edition: METRO FINAL

Section: CFP; COMMUNITY FREE PRESS

Page: 1CV

Keywords: michigan history

Disclaimer: THIS ELECTRONIC VERSION MAY DIFFER SLIGHTLY FROM THE

PRINTED ARTICLE